Knowing Your Stakeholders

Managing stakeholders is critical to the success of every plan and project, no matter the size or cost. A “stakeholder is any individual, group or organization that can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a project” as defined by the Project Management Book of Knowledge (PMBOK). Stakeholder management is the process of managing the expectations of anyone that has an interest in a plan/project or will be effected by its deliverables or outputs. By successfully managing your stakeholders, you will be better able to limit scope creep, ensure that project requirements are aligned, as well as understand and mitigate potential risks. Always remember that stakeholders can be inside or outside of ITD. Furthermore, stakeholders can have a positive or negative impact on the plan or project. Communication requirements and contact needs for stakeholders are not all the same. Let’s look at the process to identify stakeholders.

Quick Links

Click the links below to navigate to the

main topics of this chapter.

The first step in planning and project development is the identification of stakeholders. In order to accomplish this, it is important to understand what a stakeholder is. Loosely defined, a stakeholder is a person or group of people who can affect or be affected by a given plan or project.

Stakeholders can be individuals working on a project, groups of people or organizations, or a specialized segment of a population. A stakeholder may be actively involved in a plan or project’s work, affected by the plan or project’s outcome, or in a position to affect the plan or project’s success. Stakeholders can be an internal part of a project’s organization, or external, such as customers or members of a community. Do not forget that there are internal stakeholders to consider too.

Stakeholder identification is the process used to identify all interested parties for a plan or project. It is important to understand that not all stakeholders will have the same influence or effect on a project, nor will they be affected in the same manner. There are many ways to identify stakeholders for a plan or project; however, it should be done in a methodical and logical way to ensure that stakeholders are not easily omitted. This may be done by looking at stakeholders organizationally, geographically, or by involvement with various project phases or outcomes.

The table below sites some examples of stakeholders that can fall into a variety of categories. This list may be helpful when considering who you should contact or engage during the planning or project development process.

Potential Stakeholder Consideration List

ITD’s Internal Agency

- Project Managers, Sponsors and Team Members

- ITD HQ Sections

- ITD Districts

Other Dept. Partners

- Local Highway Technical Assistance Council (LHTAC)

- Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs)

- Tribal Nations and Tribal Employment Rights Offices (TEROs)

- Other Departments of Transportation

Federal

Agencies

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)

- Federal Transit Administration (FTA)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- Department of Lands

- Department of Energy and INL

- United States Postal Services

- Idaho’s Congressional Offices

Other State Agencies

- Idaho Department of Agriculture

- Idaho Department of Commerce

- Idaho Department of Environmental Quality

- Idaho Department of Fish and Game

- Idaho Department of Labor

- Idaho Department of Lands

- Idaho Legislators

- Idaho State Police

- Idaho Department of Water Resources

- Office of the Governor

- Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation

Local

Organizations

- City, County, Highway District Agencies

- Regional Planning Organizations (RPOs)

- Chambers of Commerce

- Local Land Owners, Property Owners

- Police, Fire and Emergency Services

Special

Population

- Minority Populations

- Low-Income Populations

- Elderly and Disabled Populations

- Persons with Limited English Proficiency (LEP)

- Any other specially identified group identified under Title VI or Environmental Justice

Specialized

Groups

- Professional organizations

- Bicycle/Pedestrian Alliances

- Freight and Trucking Organizations

- Providers of Public Transportation Services

- Public/Private Schools, Colleges and Universities

- Outfitters, Guides, Tourism Groups

- Media Outlets – Radio, Television, Newspaper, Internet, etc.

- Idaho Rural Partnership

- Consultants

- Associated General Contractors (AGC)

General

Public

- Any individual or group affected/impacted by the plan or project

- Any individual or group in a position to support or prevent project success

Another way of determining stakeholders is to identify those who are directly impacted by the project and those who may be indirectly affected. Directly affected stakeholders will usually have greater influence and impact on planning and project development than those indirectly affected. Those indirectly affected may include an adjacent organization or members of the local community.

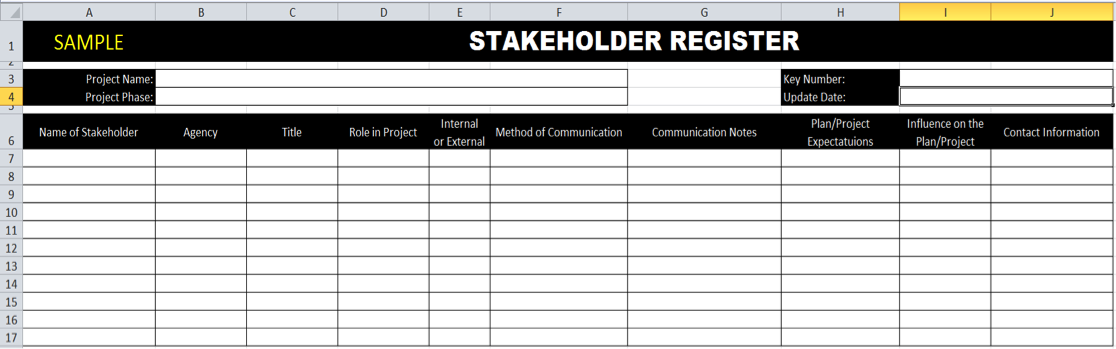

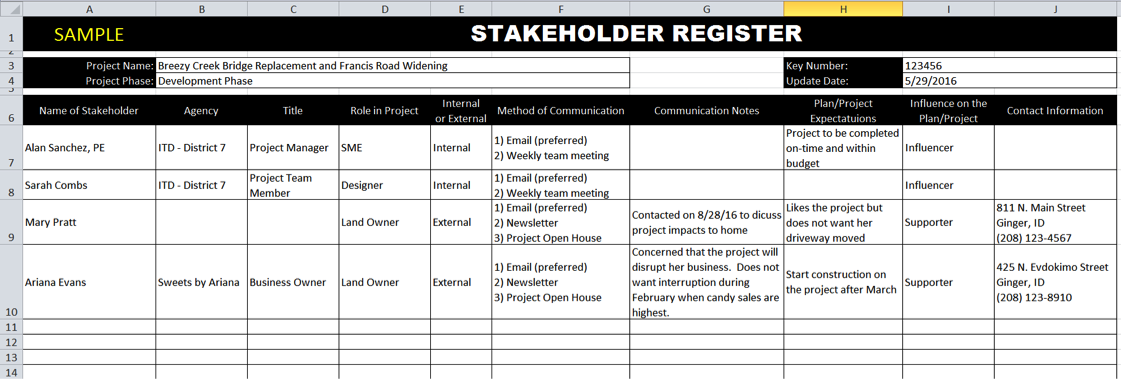

An outcome of identifying stakeholders should be a plan or project Stakeholder Register (see example below). This register can be created simply in Microsoft Excel and tracked for the life of the plan or project. The register is where the project team captures the names, contact information, titles, organizations, and other pertinent information of all stakeholders. This is a necessary tool during that will provide significant value for the project team to communicate with stakeholders in an organized manner.

Planning for and executing appropriate strategies to involve and communicate with the public-at-large and with individual stakeholders throughout the life cycle of transportation impacts is critical in ITD’s effort to maintain transparency with the public. To effectively manage public outreach plans and activities, staff needs information and recommended tools to analyze the depth and breadth of outreach needs so they can decide how best to meet them. The Public Outreach Planner (POP) is that resource and a tool.

The POP is intended to assist ITD staff in assessing the range of outreach needs, identifying tools that may be used in meeting those needs, and providing an estimate of the potential costs associated with their implementation. POP Levels and their recommendations are not mandated and staff are not held to any requirements. The POP is a resource designed to help ITD staff make educated decisions about public outreach.

Through a series of customized multiple-choice questions, the POP guides project teams to a POP Level of 1 through 5. Each level provides recommended budget estimates, staffing needs and appropriate tools and techniques for various types of transportation impacts. Through the POP, project teams can not only determine what public involvement methods and tools are the best fit for their project and budget, but they can learn more about how to effectively design, develop and execute them.

Every transportation impact has its own unique community and stakeholders that need to be communicated with in a way that produces constructive public involvement and builds understanding about the need for transportation funding. The POP prompts users to reflect on their targeted public and make determinations about what communication techniques will be the most effective.

More information on how to use the POP, including steps to complete the POP, can be found in Appendix F.

Environmental Justice Populations

There are some very important stakeholders that we need to consider that may not regularly attend meetings, hearings or outreach opportunities. These special groups may need extra special outreach processes to engage them. Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and President’s Executive Order (EO) 12898 Environmental Justice (EJ) identify specific population groups that are a special focus in transportation planning and project development. Specific reporting requirements within these regulations make participation in transportation planning and project development more inclusive of diverse communities in planning and project areas. By including the concerns of these special populations, the needs of all groups and individuals regardless of race, age, income, etc., can be identified and addressed.

Affected Groups to Consider:

High-Poverty and Racial Minority Groups | Indigenous Populations | Very Young and Elderly Groups | Limited English Proficiency Groups | Disabled Populations |

To meet the needs of the Title VI and EO 12898, ITD has developed these guidelines and the ITD Environmental Process Manual, Section 2000. These two plans provide guidance for ITD staff, public, consultants and jurisdictional partners when conducting Title VI and EJ activities for the transportation planning and project process. The approach to identify, engage, and address the needs of protected populations in the development of ITD statewide policy, facility, local and regional transportation system, and similar long-range planning plans are also addressed in these plans. ITD’s goal is to be inclusive of all groups, and achieve greater consistency and more systematic Title VI and EJ project analyses and reporting.

ITD addresses EJ throughout the planning, programming, environmental, and preliminary engineering phases of project scoping and development. During the project planning process, effects on EJ populations are identified. In addition to a project-by-project analysis, ITD is responsible for ensuring that its overall Transportation Investment Plan does not disproportionately distribute benefits or negative effects to any EJ population.

EJ is reviewed for every project however; the complexity of a project will determine the extent of EJ analysis required. ITD’s Environmental Process Manual, Section 2000 provides a methodology for analyzing EJ communities per project. The analysis typically involves identifying populations then analyzing whether the risk of exposure by a minority population or low-income population to an environmental hazard is significant and appreciably exceeds, or is likely to appreciably exceed, the risk or rate to the general population or another appropriate comparison group. Public meetings are also held to ensure an EJ community potentially impacted by a project has an opportunity for input during the NEPA process.

A full overview of ITD’s Environmental Justice Guidelines can be found in Appendix C.

Metropolitan Planning Organizations

A Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is an association of local agencies that coordinate transportation planning and development activities within a metropolitan area. Establishment of an MPO is required by law in urban areas with populations of more than 50,000 in order for the area to use federal transportation funding. There are five MPOs in Idaho:

- Bannock Transportation Planning Organization (BTPO) Visit site

- Bonneville Metropolitan Planning Organization (BMPO) Visit site

- Community Planning Association of Southwest Idaho (COMPASS) Visit site

- Kootenai Metropolitan Planning Organization (KMPO) Visit site

- Lewis-Clark Valley Metropolitan Planning Organization (LCVMPO) Visit site

MPOs are designed to ensure coordination and cooperation among the various jurisdictions that oversee transportation within the urban area. MPO decision-making is guided by:

- A policy board, generally comprised of local elected officials and public agency officials who administer or operate major modes of transportation, and

- A technical advisory group of professional planners and engineers who are often employees of the same agencies.

An MPO is not a level of government; however, the MPO has effective control over transportation improvements within their metropolitan planning area since a project must be a part of the MPO's adopted long-range plan and be placed in their Metropolitan Transportation Improvement Program (MTIP) in order to receive federal funding. According to federal regulations, MPOs have independent public involvement responsibilities. Idaho’s MPOS play an important role in coordination and consultation with ITD for transportation planning across the state, and federal law requires coordinated planning with the metropolitan transportation planning activities for metropolitan areas of the State. States are encouraged to rely on information, studies, or analyses provided by MPOs for portions of the transportation system located in metropolitan planning areas.

Because of this, ITD should look for every opportunity to engage MPOs on both the development and implementation of regional projects. Some tips and best practices for MPO consultation include:

- Coordinated data collection and analysis.

- Participation in policy board and technical advisory group meetings.

- Informal communication and relationship building with local MPO directors.

- Invitation to MPOs to participate in public meetings/open houses.

- Adequate notice of ITD public involvement activities.

- Opportunity to participate in the early development and selection of projects.

- Exploration of ways to implement long range plans together.

- Consultation with MPO directors on best practices for working district offices which could include an updated organizational chart of your district staff on an annual basis.

- Providing ITIP/STIP comments to MPOs, for informational purposes.

- Soliciting feedback on the effectiveness of ITD’s consultation with MPOs (similar to the nonmetropolitan local consultation process) as well as discussing success stories and lessons learned.

Non-Metropolitan Local Officials

ITD developed and adopted a Non-Metropolitan Local Official Consultation Process Plan in February 2016 in compliance with federal code 23 CFR450.210 (b). This regulation requires each state to have a documented process “for consulting with local officials” located outside of federally designated metropolitan planning areas during the development of statewide or district transportation plans and the ITIP. States are further required in federal code 23 CFR 450.210(b)(1) to review this process and solicit comments every five years regarding the effectiveness of the consultation.

The term “non-metropolitan local official” is defined as “the elected and appointed officials of general purpose local government, in non-metropolitan areas, with jurisdiction/responsibility for transportation.” This may include highway districts, counties, cities, towns, townships and villages.

ITD’s consultation goals are to:

- Enhance the consistency and effectiveness of ITD’s consultation commitments based on local officials’ comments during the state’s long-range transportation visioning

- Further consistency in responding to non-metropolitan transportation needs

- Outline the statewide and district-specific commitments for local consultation on the nonmetropolitan elements of statewide transportation planning

- Enrich local consultation by providing formal opportunities to review and comment on the projects to be included in the ITIP

- Comply with the provisions of 23 CFR 450.212 documenting non-metropolitan local officials’ participation in statewide transportation planning and development of the ITIP

ITD utilizes a variety of methods to consult with Non-Metropolitan Officials and their agencies:

- ITD Board Outreach & LHTAC Partnership (Appendix D)

- Multi-Jurisdictional Transportation Planning Groups

- Information – Communication Technology

- Public Meetings and Hearings

For every project that meets the Noise Type 1 criteria (ITD Traffic Noise Policy), local officials need to be notified of the results of the project’s noise analysis. In general, Noise Type 1 projects are those that add a travel through-lane to a project. It is the responsibility of the District/LHTAC environmental staff to provide local jurisdictions with an estimate of future noise levels (for various distances from the highway improvement) for both developed and undeveloped lands and properties in the immediate vicinity of the project. District/LHTAC staff should also provide information that may be useful to local communities to protect future land development from becoming incompatible with anticipated highway noise levels. The FHWA document, Entering the Quite Zone, Noise Compatible Land Use Planning, serves this purpose. This notification also serves to inform local officials that after the publication date of the NEPA document, referred to as the “Date of Public Knowledge,” ITD and FHWA are not responsible for noise abatement in the project area.

ITD’s noise policy is derived from 23 CFR Part 772 Procedures for Abatement of Highway Traffic Noise. For more specifics on Noise Type 1 projects, see the ITD Traffic Noise Policy.

Regional Planning Organizations

Regional Planning Organizations (RPOs) serve as the designated transportation planners for many rural areas, are part of the transportation networks and economies of surrounding metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. The statewide and metropolitan area transportation planning processes, as defined in 23 USC § 135(m), provide multiple opportunities for participation by RPOs or nonmetropolitan officials with responsibility for transportation participation. The Madison County RPO was formed in September 2013 and is the first of its kind in Idaho. The RPO has been an effective way for rural agencies within Madison County and ITD to jointly discuss and plan for the current and future transportation needs of the county. When the RPO was first established, they worked closely with ITD’s District 6 in planning and infrastructure discussions.

MAP-21 and the FAST Act indicate that rural areas may develop RPOs. In the cases where RPOs exist, ITD will ensure that communication, coordination and consultation will occur when developing plans and projects.

Multi-Jurisdictional Transportation Planning Groups

Each of ITD’s six districts regularly participates in several multi-jurisdictional transportation planning groups. As a member of these groups ITD provides information and collects input on ITD’s ITIP and other statewide transportation planning efforts. ITD encourages and supports the development of multi-jurisdictional transportation planning groups that include local governments responsible for transportation as well as other interests such as freight, schools, federal or state agencies to name but a few.

Where multi-jurisdictional transportation planning groups have been formed, the ITD District Engineer and/or other appropriate ITD staff will participate and consult with these groups concerning regional short and long-range transportation planning issues and the inclusion of transportation projects in the ITIP. Where these groups have not formed, the ITD district and local officials will develop alternate methods agreeable to local jurisdictions for review, prioritization and recommendation of projects to the ITIP. For details on district-specific multi-juristictional transportation planning groups, please see Appendix E.

Tribal Nations

Tribal consultation is the federally mandated process for timely and meaningful notification, consideration and discussion with tribes on actions proposed by Federal, State and local governments that may impact tribal lands and property. Tribal lands are defined as all lands within the boundaries of any Indian Reservation and all dependent Indian communities. It is important for tribal governments to be involved before these actions are taken.

Visit the Native American Consultation Database to identify federally recognized Native American tribes and contacts with reservation land or land area claims in Idaho, searchable by county.

TRIBAL SOVEREIGNTY

The basis and reason for tribal consultation is tribal sovereignty, the authority to govern themselves and to make and enforce their own laws within their own lands. Tribes have inherent sovereign authorities, which arise from tribes having been self-governing long before explorers and settlers came to the New World. Tribes are not foreign nations, but “domestic dependent nations.”

Federal Actions that protect tribal sovereignty and mandate government-to-government consultation include:

1994: Presidential Memorandum: Government-to-Government Relations with Native American Tribal Governments

This memorandum requires Federal agencies to undertake consultation in a manner that respects tribal sovereignty. Its guiding principles, shown in the text box, continue today. The memorandum is available at https://www.justice.gov/archive/otj/Presidential_Statements/presdoc1.htm

1996: Presidential Executive Order 13007: Indian Sacred Sites

This directs Federal agencies to protect tribal sacred sites and accommodate tribal access to them. The executive order is available at http://www.achp.gov/EO13007.html

2000: Presidential Executive Order 13175: Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments

This executive order mandates Federal consultation with tribal governments. The executive order is available at https://energy.gov/nepa/downloads/eo-13175-consultation-and-coordination-indian-tribal-governments-2000

2009: Presidential Memorandum on Tribal Consultation

This most recent presidential action affirms Executive Order 13175 (above) stating:

“History has shown that failure to include the voices of tribal officials in formulating policy affecting their communities has all too often led to undesirable and, at times, devastating and tragic results. By contrast, meaningful dialogue between Federal officials and tribal officials has greatly improved Federal policy toward Indian tribes. Consultation is a critical ingredient of a sound and productive Federal-tribal relationship.”

The memorandum is available at https://energy.gov/em/downloads/presidential-memorandum-tribal-consultation-2009

Outside governments, including state agencies, must respect tribal sovereignty when undertaking actions that may impact tribal lands and property.

Guiding Principles for respecting tribal sovereignty:

- Operate within a government-to-government relationship with federally-recognized tribal governments.

- Tasks: Identify communication channels between ITD’s decision-makers and a tribe’s Business Council. The Business Council is the tribes’ decision-making body, typically made up of elected officials by the tribe.

- Consult with tribal representatives before taking actions that affect federally-recognized tribes.

- Tasks: Build relationships on a staff level with tribes. Involve both staff and business council early in the project and planning process.

- Assess the impact of activities on tribal trust resources and assure that tribal interests are considered before activities are undertaken.

- Tasks: Incorporate tribal staff in project planning, design and execution.

- Remove procedural impediments to working directly with tribal governments.

- Tasks: Cultivate relationships during projects and planning and outside of project work. Building and maintaining these relationships provide for successful future project endeavors.

IMPLEMENTING TRIBAL CONSULTATION

Consultation with tribes needs to occur on two levels:

Consultation between leadership of the tribe and leadership of transportation agencies.

There needs to be a good faith effort to communicate with the tribal leadership. This communication should be documented, along with the input or comments from the tribe and reflecting how tribal concerns were taken into account.

Communication directly between agency staff and tribal staff.

The staff-to-staff level communication usually addresses technical topics, involving exchange of specific information relating to specific projects. Cultural resource issues relating to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act are the most common of these staff to staff communications.

The USDOT Tribal Consultation Plan provides direction to FHWA and the other USDOT agencies. Direction that applies at the Division/State level includes:

- Respond to the transportation concerns of tribes related to environmental justice, children’s health and safety and environmental health, occupational matters, and environmental matters.

- Contact and communicate with tribal governments; communicate with tribal leaders on emerging issues that could impact or be of interest to them.

- Seek tribal government representation in meetings, advisory committees, etc., concerning issues with tribal implications.

- Notify tribes of grant opportunities.

- Provide technical assistance to tribes on changes to legislation, regulations, and programs.

Federal Land Management Agencies

There are three primary areas where consultation needs to occur with ITD of the Interior (DOI) and other and federal land management agencies:

Right of Way: Federal Land Management agencies adjacent to ITD right-of-way oftentimes include Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (game refuges) and National Park Services (NPS). The land management agencies can’t “give away” land they manage – this includes transferring to non-federal agencies. If right-of-way is a concern with a project, contact FHWA. Once, FHWA understands ITD’s right-of-way needs, they will approach the appropriate land management agency and give them justification for why they need particular ground for public transportation purposes. Land Management agencies can transfer land easements to FHWA and FHWA can give it to ITD.

4(F) Impacts: Section 4(f) refers to the original section within the U.S. Department of Transportation Act of 1966 which established the requirement for consideration of park and recreational lands, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and historic sites in transportation project development. If there is no adverse effect, ITD can make a finding of de minimis impact. If project fits in parameters that fall within de minimis impact, FHWA approves. If the land does not qualify for de minimis impact, there are five programmatic consultations:

- Independent Bikeway or Walkway Project;

- Use of Historic Bridges (most used);

- Minor Involvement with Parks, Recreation Lands and Wildlife and Waterfowl Refuges;

- Minor Involvement with Historic Sites; and

- Transportation Projects that have a Net Benefit to a Section 4(f) Property.

An online tutorial on 4(f) Impacts is available through FHWA: https://www.environment.fhwa.dot.gov/4f/index.asp

Sect 106 National Historic Preservation Act: Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) requires consultation with any Indian tribe that attaches religious, cultural, and historic significance to properties that may be affected by an undertaking, regardless of the location of the historic property. Projects will most likely deal with the State Historic Preservation office (SHPO) if there is concern about a property affected by this act, the final authority is the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation in Washington, D.C. If 4(f) impacts and Sect 106 National Historic Preservation Act elements exist on a project, ITD should be required to provide public notice and include information on those impacts and evaluation processes in public meeting materials.

It is important to specifically reference the NHPA Act and the impacts to historic resources. When there are adverse requests, notify the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) to review and participate.

Tips and Best Practices regarding federal consultation

- Right-of-way acquisition on federal land is coordinated between agencies. It requires no public involvement with the general public.

- Always start the federal lands consultation process with FHWA, not the land owner.

- Easement acquisition on federal lands is part of the typical ITD NEPA process. Nothing special needs to be done.

- If 4(f) impacts and Sect 106 National Historic Preservation Act elements exist on a project, ITD should provide public notice and include information in public meeting materials.

- Specifically reference the NHPA Act and the impacts to historic resources. When there are adverse requests, notify the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) to review and participate.

- All Federal Lands Access Program (FLAP) funded ITD projects and FLAP funded non-ITD project with ITD support, must follow the standard ITD NEPA requirements for public involvement. FLAP projects are treated like any other federal-aid project.

Now that you have identified who your stakeholders are, you need to learn more about them and how they may feel about your plan or project. The best way to understand your stakeholders is to communicate with them. Here are a few key questions that can assist you:

- What financial or emotional interest do they have in the outcome of the plan or project. Is this positive or negative? What motivates them most of all?

- What information do they want from you? What is the best way of communicating your message to them? How often? Will you need a special communication process just for them?

- Who in the community influences their opinions generally? Are these influencers important enough to become stakeholders too?

Summarize this information in a Stakeholder Register (see example below) so that you can easily see which stakeholders are expected to be blockers or critics; and which ones are likely to be advocates or supporters of the plan or project. Again, take a close look at each stakeholder to gather more in depth information in order to understand their impact, involvement, communication requirements, and preferences. Ask yourself:

- Is this stakeholder organized? Are they a cohesive organization?

- Do they support this project or are they critical of it?

- How influential or powerful are they?

- Do they prefer to be notified via phone, email or social media? How often?

- What is this stakeholder’s interest in this project?

Stakeholder assessment is an analysis of the potential impact (positive or negative) a plan or project will have on a stakeholder. The information is used to assess how the interests of those stakeholders should be addressed in a plan or project. The benefits of using a stakeholder-based analysis are that:

- You can use the opinions of the most powerful stakeholders to shape your plan or project at an early stage. Not only does this make it more likely that they will support you, their input can also improve the quality of the plan or project.

- Gaining support from powerful stakeholders can help with obtaining additional resources such as staff or funding – which makes it more likely that the plan or project will be successful.

- By communicating with stakeholders early and frequently, you can ensure that they fully understand what you are doing and understand the benefits of the plan or project – which means they can actively support you if it becomes needed.

- You can anticipate what people’s reactions to your plan or project may be, and build into the plan or project the actions that will win stakeholder support.

Stakeholder Management is where you will use all of the information you’ve collected and develop a strategy to manage stakeholders. No matter how much you plan or how invested you are in a project, poor stakeholder management can easily cause a project to fail. It is a key component of executing and completing a successful project. A large portion of stakeholder management focuses on communication and when to reach out.

The cornerstone of stakeholder management is understanding who needs what information and when or how often they need it. Keep in mind that that there may be stakeholders who support the project and those who may either be opposed to it or who present obstacles to the project’s success. Your stakeholder management strategy must be geared toward maintaining support from those who are in favor of the plan/project while winning over those opposed or at least mitigating the risks they may present.

The questions you’ve asked and answered about each stakeholder in the Stakeholder Analysis process are your guide for how to interact with each stakeholder and satisfy their individual requirements. By determining how powerful a stakeholder is and whether or not they support or oppose the project will allow the project manager to create a strategy for communicating and working with that stakeholder to ensure project success. Some stakeholders may require little interaction or communication while some require nearly constant communication. Stakeholder Management is where these strategies are developed and executed. If a stakeholder is opposed to a project maybe it is because they seek more involvement or awareness and the project manager can work with that individual to win their favor and support.

As the plan or project becomes more complex and involved, so will your management of stakeholders. It is easy to lose track or omit key project players and by not properly utilizing these processes and tools project managers will lose their ability to effectively communicate with stakeholders in a manner necessary to ensure a successful project.

THE OUTCOME-DRIVEN PROCESS

In order to develop, write and implement an effective Public Involvement Plan, it is important to begin with the end in mind. In other words, identify and articulate exactly what the goals of the project and plan are and what criteria will best measure how well those goals were achieved.

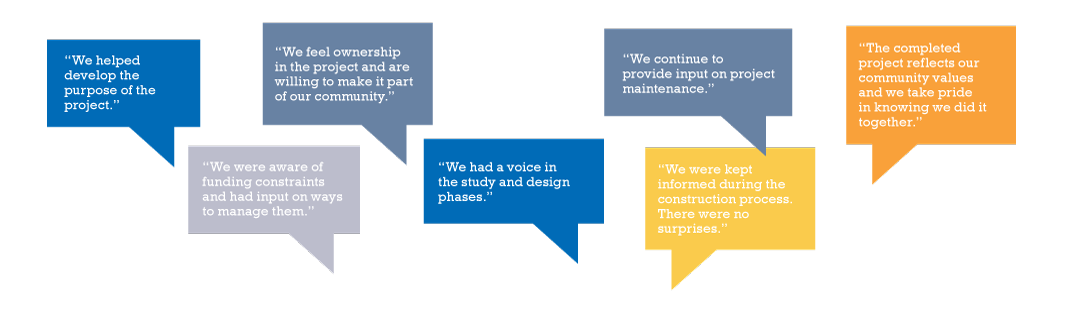

The goal of public involvement is to generate win-win solutions and comments like these:

Public Outreach Planner (POP)

Planning for and executing appropriate strategies to involve and communicate with the public-at-large and with individual stakeholders throughout the life cycle of transportation impacts is critical in ITD’s effort to maintain transparency with the public. To effectively manage public outreach plans and activities, staff need information and recommended tools to analyze the depth and breadth of outreach needs so they can decide how best to meet them. The Public Outreach Planner (POP) is that resource and a tool.

The POP is intended to assist ITD staff in assessing the range of outreach needs, identifying tools that may be used in meeting those needs, and providing an estimate of the potential costs associated with their implementation. POP Levels and their recommendations are not mandated and staff are not held to any requirements. The POP is a resource designed to help ITD staff make educated decisions about public outreach.

Through a series of customized multiple-choice questions, the POP guides project teams to a POP Level of 1 through 5. Each level provides recommended budget estimates, staffing needs and appropriate tools and techniques for various types of transportation impacts. Through the POP, project teams can not only determine what public involvement methods and tools are the best fit for their project and budget, but they can learn more about how to effectively design, develop and execute them.

Every transportation impact has its own unique community and stakeholders that need to be communicated with in a way that produces constructive public involvement and builds understanding about the need for transportation funding. The POP prompts users to reflect on their targeted public and make determinations about what communication techniques will be the most effective. ITD recommends that the POP process be reevaluated as projects evolve and change from one phase to the next and sometimes within a single phase. ITD also recommends that public involvement plans be re-evaluated to reflect POP recommendations and changes in the project. For a long process, built-in formal revision dates are a good idea.

More information on how to use the POP, including steps to complete the POP, can be in Appendix F.

Development of a Public Involvement Plan

Every transportation project is different and each requires a public involvement plan tailored to its own unique needs and issues. Thorough scoping helps project managers ask the questions that are critical to a project’s success. It provides the information necessary to write a public involvement plan that takes recommendations from the POP to guide future public involvement activities, budgets and schedules. If conducted before a consultant is hired, scoping data help ITD determine which consultant could provide the best public involvement services. It also allows project managers to better analyse a consultant’s scope of work.

Detailing public involvement goals, objectives, strategies and tools helps ensure that methods for soliciting public input are effective. With up-front planning, mid-stream changes are less likely, meaning that projects are more likely to stay within budget and on schedule.

An effective public involvement plan must coordinate with the technical milestones in the planning process or the project development process. Coordination means that a good schedule with well-defined activities is critical.

Flexibility is also critical. Effective public involvement activities should be adaptable so they can evolve as conditions and situations change. Begin developing a plan by identifying the project’s purpose and need, determining the level of public involvement appropriate for the project through the POP, and identifying public involvement goals and objectives. Clarity will help identify the best strategy and tactics.

- Complete the POP before you start writing the public involvement plan.

- A plan is required for complex transportation projects and highly recommended, but not required, for all other projects.

- The public involvement coordinator is available for help in completing the public involvement plan.

- Submit the completed plan to the public involvement coordinator and attach a copy of the Location and/or Design Study Report.

Components of a Public Involvement Plan include

- Project Introduction

- Goals & Objectives

- Project Stakeholders

- Project Strategy

- Staffing & Tools

- Resources

- Project Schedule

- Management

- Evaluation

Project managers can request the public involvement coordinator’s participation in projects whether or not a consultant is involvement in a project. The public involvement coordinator is responsible for reviewing and providing feedback to the project manager regarding any consultant’s scope of work and a public involvement plan.

For an in-depth, step-by-step guide to developing your customized public involvement, plan, please see Appendix G.